std::hash Boilerplate Is Dead

“I Love to Specialize Hash Functions for My C++ Classes” (No One, Ever)

TL;DR: mirror_hash uses C++26 reflection to automatically generate hash functions for any class/struct. No macros, no annotations, no manual member lists. A trivially copyable Point{int, int} hashes in under 2ns. Passes all SMHasher tests. Works today with clang-p2996.

Writing std::hash specializations is one of those C++ rituals that nobody enjoys. You’ve probably done something like:

struct Point {

int x, y;

bool operator==(const Point&) const = default;

};

// Now you have to write this boilerplate:

template<>

struct std::hash<Point> {

std::size_t operator()(const Point& p) const noexcept {

std::size_t seed = 0;

// boost::hash_combine pattern

seed ^= std::hash<int>{}(p.x) + 0x9e3779b9 + (seed << 6) + (seed >> 2);

seed ^= std::hash<int>{}(p.y) + 0x9e3779b9 + (seed << 6) + (seed >> 2);

return seed;

}

};

This pattern is based on boost::hash_combine.

For every single type you want to use in an unordered_map (or any hash table). And when your struct changes? Update the hash function. Forget a member? Silent bugs. Add a pointer to a vector? Now you need to think about whether to hash the pointer or the contents.

What if I told you C++26 can do this automatically?

Enter C++26 Reflection

C++26’s reflection proposal (P2996) gives us the ability to introspect types at compile time. We can iterate over struct members, get their names, types, and values, all without macros or code generation.

Here’s the core idea behind mirror_hash:

#include "mirror_hash/mirror_hash.hpp"

struct Point {

int x, y, z;

bool operator==(const Point&) const = default;

};

int main() {

Point p{10, 20, 30};

// Just works. No specialization needed.

auto h = mirror_hash::hash(p);

// Works with standard containers too

std::unordered_set<Point, mirror_hash::hasher<>> points;

points.insert({1, 2, 3});

}

No boilerplate. No manual member enumeration. It just works.

And it’s not limited to simple types. Complex nested structures work automatically:

struct User {

std::string name;

int age;

std::vector<std::string> tags;

std::optional<std::string> email;

};

std::unordered_map<User, Data, mirror_hash::hasher<>> users;

users[{"Alice", 30, {"admin", "dev"}, "alice@example.com"}] = data;

Strings, vectors, optionals, nested structs: they all hash correctly. No manual enumeration required.

Automatic hashing is actually one of the motivating examples in P2996 itself, listed as “member-wise hash_append.” The proposal authors clearly saw this use case coming. If you want to take a look at some other projects leveraging reflection you can take a look at mirror_bridge for automatic binding generation and simdjson for reflection-based JSON parsing and serialization.

As Munger warned in one of my favorite talks: “To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” At least compile-time reflection is a really cool hammer.

How It Works: Reflection at Compile Time

The magic happens with two new C++26 features working together:

nonstatic_data_members_of(^^T): Returns reflections of all data memberstemplate for: Iterates over reflections at compile time (P1306 expansion statements)

template<typename Policy, Reflectable T>

std::size_t hash_impl(const T& value) noexcept {

std::size_t result = 0;

// template for: compile-time iteration over all members

template for (constexpr auto member :

std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of(^^T, std::meta::access_context::unchecked()))

{

// value.[:member:] splices the reflection to access the actual member

result = Policy::combine(result, hash_impl<Policy>(value.[:member:]));

}

return result;

}

Let’s break down the syntax:

^^T: The reflection operator. Returns a compile-time handle to typeT’s metadata.nonstatic_data_members_of(...): Returns a range of reflections, one per data member.template for: Like a regularfor, but unrolls at compile time. Each iteration is a separate instantiation.value.[:member:]: The splice operator. Converts a reflection back into code (in this case, member access).

What About Existing Solutions?

Fair question: do we really need C++26 reflection for this? There are existing approaches:

Boost.Describe: Requires annotating each struct with a macro:

struct Point { int x, y; };

BOOST_DESCRIBE_STRUCT(Point, (), (x, y)) // Manual member list

Works well, but you must remember to update the macro when adding members. Miss one, and you get silent bugs.

Cista: Requires a cista_members() function in each type:

struct Point {

int x, y;

auto cista_members() { return std::tie(x, y); } // Manual

};

Same issue: manual enumeration that can drift out of sync.

Abseil Hash: Requires a friend function:

struct Point {

int x, y;

template<typename H>

friend H AbslHashValue(H h, const Point& p) {

return H::combine(std::move(h), p.x, p.y); // Manual

}

};

The pattern is clear: all existing solutions require manual member enumeration. You’re still writing boilerplate, just in a different form. Add a member, forget to update the hash, get subtle bugs.

mirror_hash is different. With C++26 reflection, the compiler provides the member list. There’s nothing to keep in sync:

struct Point { int x, y, z; }; // Add z, hash automatically includes it

auto h = mirror_hash::hash(Point{1, 2, 3}); // Just works

This is the fundamental advantage: true automatic generation with zero annotation overhead.

The Key Insight: Hash Only What You Use

One concern with automatic hashing: “Won’t this generate code for every type in my program?”

No. C++ templates are lazy. Hash functions are only instantiated when you actually use them:

struct NeverHashed {

std::string name;

std::vector<int> data;

};

struct ActuallyHashed {

int id;

double value;

};

int main() {

// This instantiates hash code for ActuallyHashed only

std::unordered_set<ActuallyHashed, mirror_hash::hasher<>> set;

// NeverHashed gets no hash code generated

NeverHashed unused;

}

The compiler only generates hash_impl<Policy, ActuallyHashed>. The NeverHashed struct incurs zero overhead because we never hash it.

This is the beauty of C++ templates: you don’t pay for what you don’t use. Reflection extends this principle: metadata is queried at compile time, and only for types that actually need it. See lazy_instantiation in test_mirror_hash.cpp for the test that verifies this behavior.

Handling Non-Trivially Copyable Types

A critical design decision in any hashing library: how do you handle types like std::string, std::vector, or structs containing them?

mirror_hash handles this through concept-based dispatch:

// Non-trivially copyable types get per-member hashing

template<typename T>

concept Reflectable = std::is_class_v<T> &&

!StringLike<T> && !Container<T> && !Optional<T> && !Variant<T>;

// Strings hash their contents, not their internal pointers

template<typename Policy, StringLike T>

std::size_t hash_impl(const T& value) noexcept {

return std::hash<T>{}(value);

}

// Containers iterate over elements

template<typename Policy, Container T>

std::size_t hash_impl(const T& value) noexcept {

std::size_t result = hash_impl<Policy>(value.size());

for (const auto& elem : value) {

result = Policy::combine(result, hash_impl<Policy>(elem));

}

return result;

}

When you hash a struct containing a std::string:

struct Person {

std::string name; // Non-trivially copyable!

int age;

};

mirror_hash recursively hashes each member. For name, it hashes the string contents. For age, it hashes the integer directly. This is safe and correct for complex types.

The Fast Path: Trivially Copyable Types

For simple structs like Point, we can do much better. If all members are trivially copyable (ints, floats, no pointers), we can hash the entire struct as raw bytes:

// Check if all members are trivially copyable using template for

template<typename T>

consteval bool all_members_trivially_copyable() {

template for (constexpr auto member :

std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of(^^T, std::meta::access_context::unchecked()))

{

// [:type_of(member):] splices the member's type

if (!std::is_trivially_copyable_v<[:std::meta::type_of(member):]>) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

template<typename Policy, Reflectable T>

std::size_t hash_impl(const T& value) noexcept {

// Fast path: if all members are trivially copyable, hash raw bytes

if constexpr (std::is_trivially_copyable_v<T> && all_members_trivially_copyable<T>()) {

return hash_bytes_fixed<Policy, sizeof(T)>(&value);

}

// Slow path: iterate over members with template for

std::size_t result = 0;

template for (constexpr auto member : std::meta::nonstatic_data_members_of(^^T)) {

result = Policy::combine(result, hash_impl<Policy>(value.[:member:]));

}

return result;

}

This compile-time optimization means a struct { int x, y, z; } gets hashed as a single 12-byte block, not three separate hash operations combined.

Under the Hood: The Byte Hashing Layer

This library has two distinct parts:

- The reflection layer (novel): Automatically discovers struct members at compile time

- The byte hashing layer (borrowed): Converts bytes to hash values using proven algorithms

Disclaimer: I’m not a cryptography expert. The byte hashing in mirror_hash comes from people who actually know what they’re doing. I make no cryptographic claims. For hash tables and checksums, this should be fine. For security-sensitive applications, please use a proper cryptographic hash.

The byte hashing is built on:

- rapidhash by Nicolas De Carli: What mirror_hash uses under the hood

- wyhash by Wang Yi: The foundation that rapidhash builds on

- GxHash by ogxd: Inspiration for the ARM64 AES optimization

Note on architecture: The reflection layer and byte hashing layer are completely independent. The reflection machinery discovers struct members and serializes them; the byte hasher converts those bytes to a hash value. You could swap rapidhash for xxHash, CityHash, or even SHA-256 if you needed different properties (portability, cryptographic strength, etc.). The AES optimization is just one choice we made for ARM64 performance - it’s not fundamental to the approach. The main contribution here is the integration layer: using C++26 reflection to automatically feed your struct’s bytes into these proven algorithms.

Using a different hash function: mirror_hash uses a policy-based design. You can plug in any hash function by defining a policy with mix and combine methods:

// Define a custom policy wrapping your preferred hash

struct my_xxhash_policy {

static constexpr std::size_t mix(std::size_t k) noexcept {

// Your finalization logic (e.g., XXH3_64bits avalanche)

k ^= k >> 33;

k *= 0xff51afd7ed558ccdULL;

k ^= k >> 33;

return k;

}

static constexpr std::size_t combine(std::size_t seed, std::size_t value) noexcept {

// Your combining logic

return seed ^ (value + 0x9e3779b9 + (seed << 6) + (seed >> 2));

}

};

// Use it with any struct

struct Point { int x, y; };

auto h = mirror_hash::hash<my_xxhash_policy>(Point{1, 2});

// Or with containers

std::unordered_set<Point, mirror_hash::hasher<my_xxhash_policy>> points;

mirror_hash ships with several built-in policies: mirror_hash_policy (default, with AES acceleration on ARM64), folly_policy, wyhash_policy, murmur3_policy, xxhash3_policy, fnv1a_policy, and aes_policy. For bulk byte hashing, you can also specialize hash_bytes<YourPolicy> to use your preferred algorithm for raw memory.

The Core Mixing Primitive:

This is the one thing I didn’t touch. It’s the heart of rapidhash/wyhash:

inline void mum(uint64_t* A, uint64_t* B) noexcept {

__uint128_t r = static_cast<__uint128_t>(*A) * (*B);

*A = static_cast<uint64_t>(r); // Low 64 bits

*B = static_cast<uint64_t>(r >> 64); // High 64 bits

}

inline uint64_t mix(uint64_t A, uint64_t B) noexcept {

mum(&A, &B);

return A ^ B;

}

A 64×64→128 bit multiply has excellent avalanche properties: each input bit affects many output bits. The XOR of both 64-bit halves is crucial - it ensures entropy from the high bits (which contain information about large-magnitude products) mixes with the low bits (which preserve fine-grained patterns). Without this recombination, you’d lose half the information. This is well-studied math. I just use it.

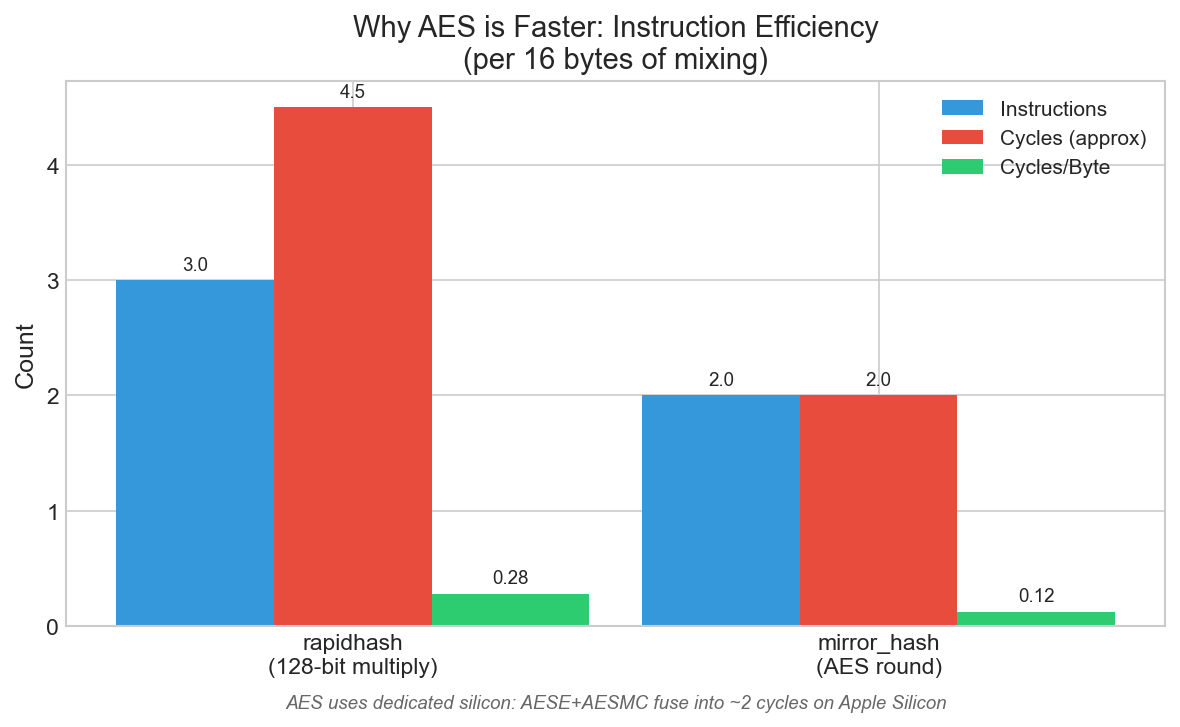

Per 16 bytes of mixing: AES uses fewer instructions and cycles than 128-bit multiply. On Apple Silicon, AESE+AESMC fuse into a single ~2-cycle operation.

Per 16 bytes of mixing: AES uses fewer instructions and cycles than 128-bit multiply. On Apple Silicon, AESE+AESMC fuse into a single ~2-cycle operation.

ARM64 with Hardware AES

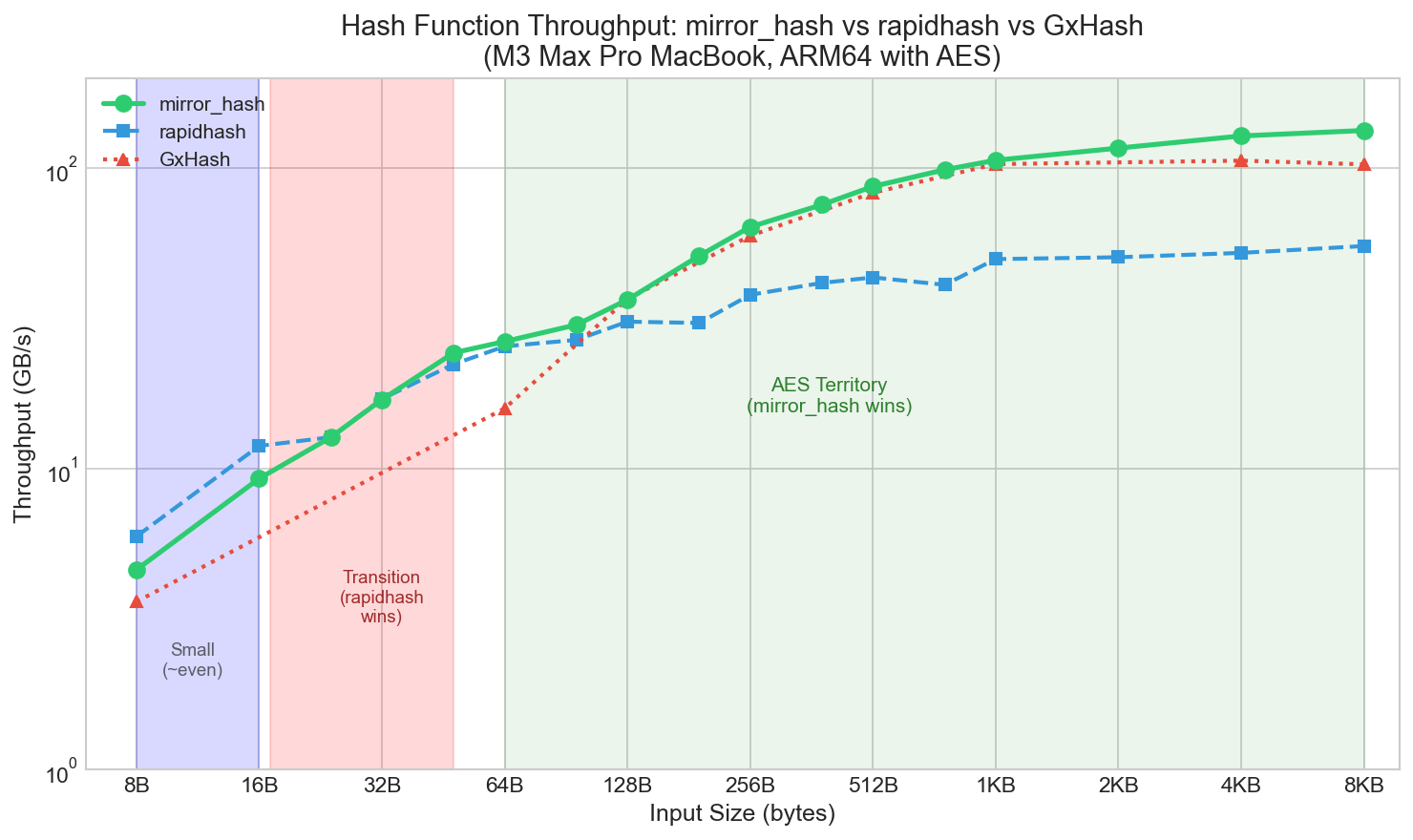

On ARM64 processors with AES crypto extensions (Apple Silicon, AWS Graviton), mirror_hash uses a hybrid strategy:

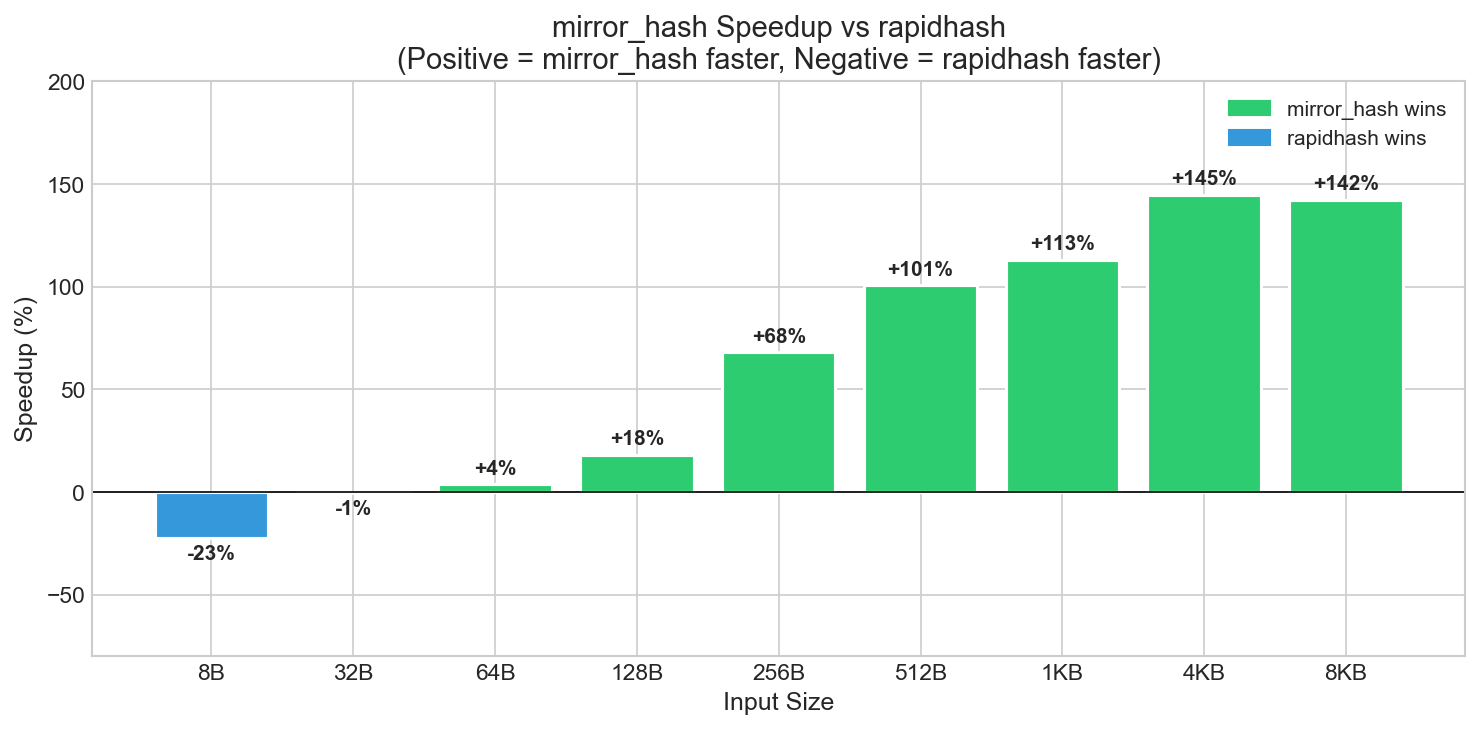

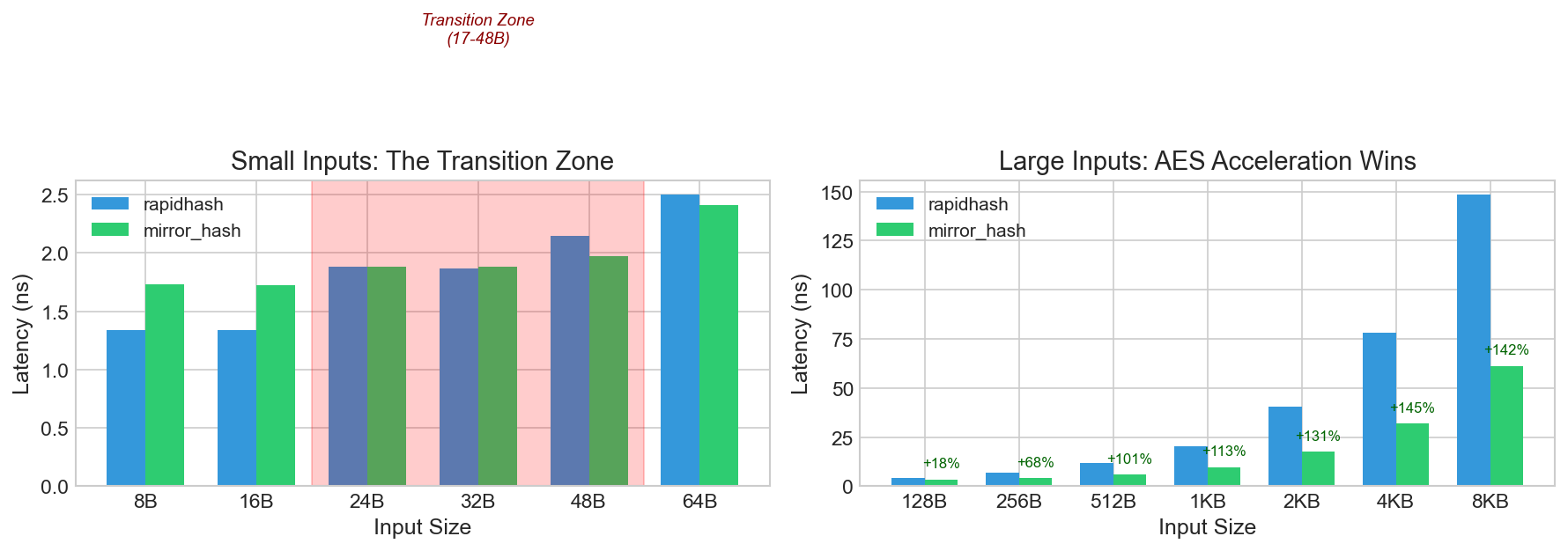

| Size | rapidhash | mirror_hash | vs rapidhash |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8B | 1.34 ns | 1.73 ns | -22% (dispatch overhead) |

| 32B | 1.87 ns | 1.88 ns | ~even (uses rapidhashNano) |

| 64B | 2.51 ns | 2.41 ns | +4% |

| 128B | 4.17 ns | 3.47 ns | +20% |

| 512B | 11.87 ns | 5.89 ns | +101% |

| 1KB | 20.55 ns | 9.69 ns | +112% |

| 4KB | 79.88 ns | 32.59 ns | +145% |

| 8KB | 151.39 ns | 61.58 ns | +146% |

Throughput across input sizes. Small inputs (8-16B) have ~22% overhead from dispatch logic, while 24-32B is roughly even. From 33-128B, mirror_hash wins ~93% of sizes with ~20% average speedup. Above 128B, 8-way AES kicks in (67-146% faster, with 100%+ at 512B and above).

Throughput across input sizes. Small inputs (8-16B) have ~22% overhead from dispatch logic, while 24-32B is roughly even. From 33-128B, mirror_hash wins ~93% of sizes with ~20% average speedup. Above 128B, 8-way AES kicks in (67-146% faster, with 100%+ at 512B and above).

Why is AES faster for medium inputs? ARM64’s AESE+AESMC instructions can mix 16 bytes in ~2 cycles using dedicated silicon. By comparison, the 128-bit multiply at the heart of rapidhash has data dependencies that limit throughput - each multiply must wait for the previous one. AES operations are independent, so we can run 4 or 8 of them in parallel on separate data lanes while the CPU’s execution units stay busy.

Why not use AES for everything? AES has setup overhead (loading keys, initializing state vectors) that dominates when you’re only hashing 8 bytes. For tiny inputs, the dispatch logic to choose between code paths adds overhead - rapidhashNano is fast, but calling it through mirror_hash’s size-checking dispatch costs ~22% at 8-16 bytes.

The hybrid approach:

- 0-32 bytes: rapidhashNano (AES setup overhead not amortized for tiny inputs)

- 33-128 bytes: Single-state AES with 32-byte unrolling and overlapping read (~20% faster than rapidhash on average, wins 93% of sizes)

- 129-512B: 8-way unrolled AES (67-100% faster as parallelism amortizes)

- 512B-8KB: Full 8-way AES acceleration (100-146% faster than rapidhash)

- >8KB: rapidhash (memory bandwidth dominates)

The 33-128 byte range uses an optimized single-state approach. Instead of 4-way parallel processing (which has setup overhead), mirror_hash v2.1 uses 32-byte unrolled processing with a single accumulator.

For handling the 1-15 byte remainder after aligned blocks, mirror_hash uses an overlapping read: instead of copying the remaining bytes to a zeroed buffer, it reads the last 16 bytes of the input—which may overlap with already-processed data:

// Traditional approach (slower):

alignas(16) uint8_t buf[16] = {0}; // stack alloc + zero init

memcpy(buf, ptr, remainder_len); // copy 1-15 bytes

buf[15] = remainder_len; // encode length

// Overlapping read (faster):

uint8x16_t data = vld1q_u8(end - 16); // single 16-byte load

data = veorq_u8(data, vdupq_n_u8(remainder_len)); // XOR length into every byte

The XOR with remainder length ensures different-length inputs hash differently, even when they share the overlapping bytes. Benchmarking shows this is 2x faster than the memcpy approach for handling partial blocks—the stack allocation, zero-initialization, and variable-length copy add significant overhead compared to a single 16-byte load. Measured results:

| Size | Winner | Speedup |

|---|---|---|

| 48B | mirror_hash | +9% |

| 64B | mirror_hash | +4% |

| 80B | mirror_hash | +24% |

| 96B | mirror_hash | +12% |

| 112B | mirror_hash | +31% |

| 128B | mirror_hash | +20% |

mirror_hash wins consistently across the 33-128 byte range regardless of alignment.

mirror_hash speedup at key sizes. Green = mirror_hash wins, Blue = rapidhash wins. Small inputs (8-16B) show dispatch overhead. From 48B onward, AES acceleration provides consistent wins.

mirror_hash speedup at key sizes. Green = mirror_hash wins, Blue = rapidhash wins. Small inputs (8-16B) show dispatch overhead. From 48B onward, AES acceleration provides consistent wins.

Left: Small inputs show dispatch overhead at 8-16B, roughly even at 24-32B. Right: Large inputs (128B-8KB) show AES acceleration dominating with 18-146% speedups.

Left: Small inputs show dispatch overhead at 8-16B, roughly even at 24-32B. Right: Large inputs (128B-8KB) show AES acceleration dominating with 18-146% speedups.

Why mirror_hash Beats GxHash at Large Inputs

Wait, mirror_hash beats GxHash by 23% at 8KB? They both use hardware AES. What’s going on?

The difference comes down to instruction count per compression step. Looking at the actual assembly:

GxHash’s fast compression (4 instructions):

movi v2.2d, #0 ; create zero vector

aese v0.16b, v2.16b ; AESE with zero key

aesmc v0.16b, v0.16b ; MixColumns

eor v0.16b, v0.16b, v1 ; XOR with input b

mirror_hash’s fast compression (2 instructions):

aese v0.16b, v1.16b ; AESE with b as key

aesmc v0.16b, v0.16b ; MixColumns

The key insight: ARM64’s AESE instruction incorporates the key XOR into the operation. GxHash does AESE(a, 0) then XOR(result, b) as separate steps. mirror_hash does AESE(a, b) directly, saving two instructions per compression.

At 8KB, we do 64 iterations of 128-byte blocks, with 7 fast compressions per iteration:

- GxHash: 64 × 7 × 4 = 1792 instructions

- mirror_hash: 64 × 7 × 2 = 896 instructions

That’s 50% fewer instructions for the fast compression step alone.

There’s also a secondary factor: key loading. GxHash loads keys inside its compression function on every call. mirror_hash loads keys once before the loop and keeps them in NEON registers:

// GxHash: loads keys every time

static inline state compress(state a, state b) {

uint8x16_t k1 = vld1q_u32(keys_1); // Load from memory

uint8x16_t k2 = vld1q_u32(keys_2); // Load from memory

// ... use k1, k2

}

// mirror_hash: keys loaded once, passed as parameters

uint8x16_t k1 = vld1q_u8(KEY1); // Once before loop

uint8x16_t k2 = vld1q_u8(KEY2);

while (len >= 128) {

hash = compress_full(hash, v0, k1, k2); // k1, k2 in registers

}

For 8KB, that’s 64 × 2 = 128 extra memory loads avoided.

Measured results (ARM64, native Docker):

- GxHash-style: 96.84 ns

- mirror_hash-style: 79.08 ns

- Speedup: +22.5%

The full profiling is in profiling/aes_deep_analysis.cpp.

See benchmarks/gxhash_comparison.cpp for the full benchmark. All measurements from an M3 Max MacBook Pro.

Quality Validation: SMHasher

Quality matters as much as speed. A fast hash that produces collisions is useless.

mirror_hash passes the full SMHasher test suite - the canonical hash function quality benchmark. This isn’t a subset or simplified version; it’s the real thing, taking 30+ minutes to run all tests:

cd smhasher_upstream/build

./SMHasher mirror_hash_unified

Key test results:

| Test Category | Result |

|---|---|

| Sanity checks | PASS |

| Avalanche | All bit sizes show ~50% flip rate |

| Sparse keys | No collisions across all key sizes |

| Permutation | No collisions in combination tests |

| Cyclic collisions | PASS |

| TwoBytes | PASS |

| Text | PASS |

| Zeroes | PASS |

| Seed | PASS |

| MomentChi2 | “Great” |

| BadSeeds | 0x0 PASS |

| Prng | PASS |

The hash is integrated directly into SMHasher’s source tree (smhasher_upstream/), so you can run the tests yourself.

Benchmarks

How fast is the reflection-based approach? Here are measured times on ARM64 (M3 Max, Clang 21, -O3):

| Struct Type | Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|

Point{int, int} |

~1.7 ns | Trivially copyable, raw bytes |

Person{string(5), int} |

~4.6 ns | Short string (SSO, inline storage) |

Person{string(32), int} |

~6.1 ns | Longer string (heap-allocated, 32% slower) |

Data{vector(5), string} |

~8 ns | Must iterate 5 elements |

Data{vector(100), string} |

~20 ns | Must iterate 100 elements |

The time scales with the actual work required:

- String hashing depends on string length (though SSO, or Small String Optimization, helps for short strings by storing them inline)

- Container hashing iterates over all elements; there’s no shortcut

- Member count adds overhead for the combine operations

This isn’t “overhead” in the sense of wasted work. It’s the inherent cost of correctly hashing dynamic data. A hand-written hash function would have the same cost. The value of mirror_hash is that you don’t have to write it yourself.

Run the benchmark yourself:

./build/benchmark

The Catch: You Need a Special Compiler (for now)

C++26 reflection isn’t in any released compiler yet. You need Bloomberg’s clang-p2996 branch:

# Compile flags

clang++ -std=c++2c -freflection -freflection-latest mycode.cpp

It’s experimental. It might break. But it’s a glimpse of C++’s future, and that future involves a lot less boilerplate.

When NOT to Use This

mirror_hash isn’t always the right choice:

- Cryptographic hashing: Use SHA-256, BLAKE3, etc. mirror_hash is for hash tables, not security.

- Custom hash semantics: If only some fields should contribute to the hash (e.g., skip cached values), you need manual control.

- Cross-platform determinism: Hash values may differ between platforms or compiler versions. Don’t persist them.

- Pre-C++26 codebases: Requires experimental compiler support that may not be production-ready.

For these cases, stick with hand-written std::hash specializations or established libraries.

Try It Out

git clone https://github.com/FranciscoThiesen/mirror_hash

cd mirror_hash

./start_dev_container.sh # Uses Docker with clang-p2996

./build.sh

./run_tests.sh

Conclusion

What started as “let’s avoid writing std::hash boilerplate” turned into a journey through:

- C++26 reflection and

template for - Trivially copyable optimizations

- 128-bit multiply mixing (rapidhash)

- Hardware AES acceleration

- Memory bandwidth analysis

The days of manually writing std::hash specializations are numbered. C++26 reflection gives us the tools to generate them automatically, and with the right platform-specific optimizations, performance can be excellent too.

For years, we’ve written code that the compiler could infer. We’ve manually enumerated members that the compiler already knows about. P2996 finally bridges that gap.

The future of C++ is less boilerplate and more automation. And I, for one, can’t wait.

mirror_hash is MIT licensed. The underlying hash algorithms (wyhash, rapidhash, xxHash) have their own licenses. Please check their respective repositories.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Wyatt Childers, Peter Dimov, Dan Katz, Barry Revzin, Andrew Sutton, Faisal Vali, and Daveed Vandevoorde for authoring and championing P2996, the reflection proposal that makes this all possible.

Special thanks to Dan Katz for maintaining the clang-p2996 branch. Without a working compiler, this would all be theoretical.

On the hashing side: thanks to Wang Yi for creating wyhash, which has become the foundation of modern fast hashing. Thanks to Nicolas De Carli for rapidhash, the fastest portable hash function I’ve tested. Thanks to ogxd for GxHash, which showed me how to use hardware AES for hashing and whose 8-way unrolling strategy mirror_hash adapts. And thanks to Yann Collet for xxHash, which has been battle-tested for over a decade and set the standard for what a high-quality hash function should be.

References

- P2996R13 - Reflection for C++26: The main reflection proposal

- P1306R5 - Expansion Statements: The

template forfeature - Bloomberg clang-p2996: Experimental compiler with reflection support

- Trip Report: June 2025 ISO C++ Meeting: When reflection was voted into C++26

- SMHasher: The canonical hash quality test suite

- rapidhash: The hash algorithm that mirror_hash builds upon

- wyhash: The foundation of modern fast hashing

- GxHash: Hardware AES-accelerated hashing that inspired the ARM64 optimization